America’s Foster Care System >>

<< Is the Pipeline for Child Sex Trafficking >>

"No one looks for us. I really want to make this clear. No one looks for us." -T. Ortiz Walker Pettigrew

>> Executive Summary

The manifestations of human trafficking are multifaceted and vary across geographic locations, ethnic and cultural groups, and socioeconomic statuses. The United States is considered a host, transit, and destination country in which domestic-born and foreign nationals, transported both legally and illegally, are exploited in the United States by domestic and foreign traffickers. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of domestic-born children are at risk of being sex trafficked within the United States each year. There has been particular focus on antecedents to sex trafficking such as poverty, involvement with the child welfare system, histories of child sexual abuse, access to technology, among others. In the context of this report, “human trafficking” and “trafficking in persons” will be used interchangeably as umbrella terms that encompass both forced labor and commercial sexual exploitation. Human trafficking can be defined as the commercial sexual exploitation and/or forced labor of individuals where force, fraud, or coercive measures (with important caveats for minors) induce a victim’s participation in sexual or nonsexual work in exchange for something of value such as money, amenities, or basic needs (e.g. food and shelter). The terms “commercial sexual exploitation” and “sex trafficking” will be used interchangeably when discussing the women, men, girls, boys, and transgender individuals whose bodies have been sexually exploited in a commercial exchange. The term commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) will encompass all minors under the age of 18 who have been sexually exploited regardless of the presence of a trafficker, the use of force, fraud, or coercion, or transportation across physical boundaries. The term “victim” is employed when discussing an adult or minor during their exploitation; subsequently, the term “survivor” denotes any individual who has exited the exploitation. Exploiter and trafficker will refer to the person, different than the victim, which benefits from the exploitation whether they are facilitating the commercial activity or sexually benefiting from the sex acts. A database of sources leveraged for the production of this report can be found at Human Trafficking Data.

>> Introduction to Human Trafficking

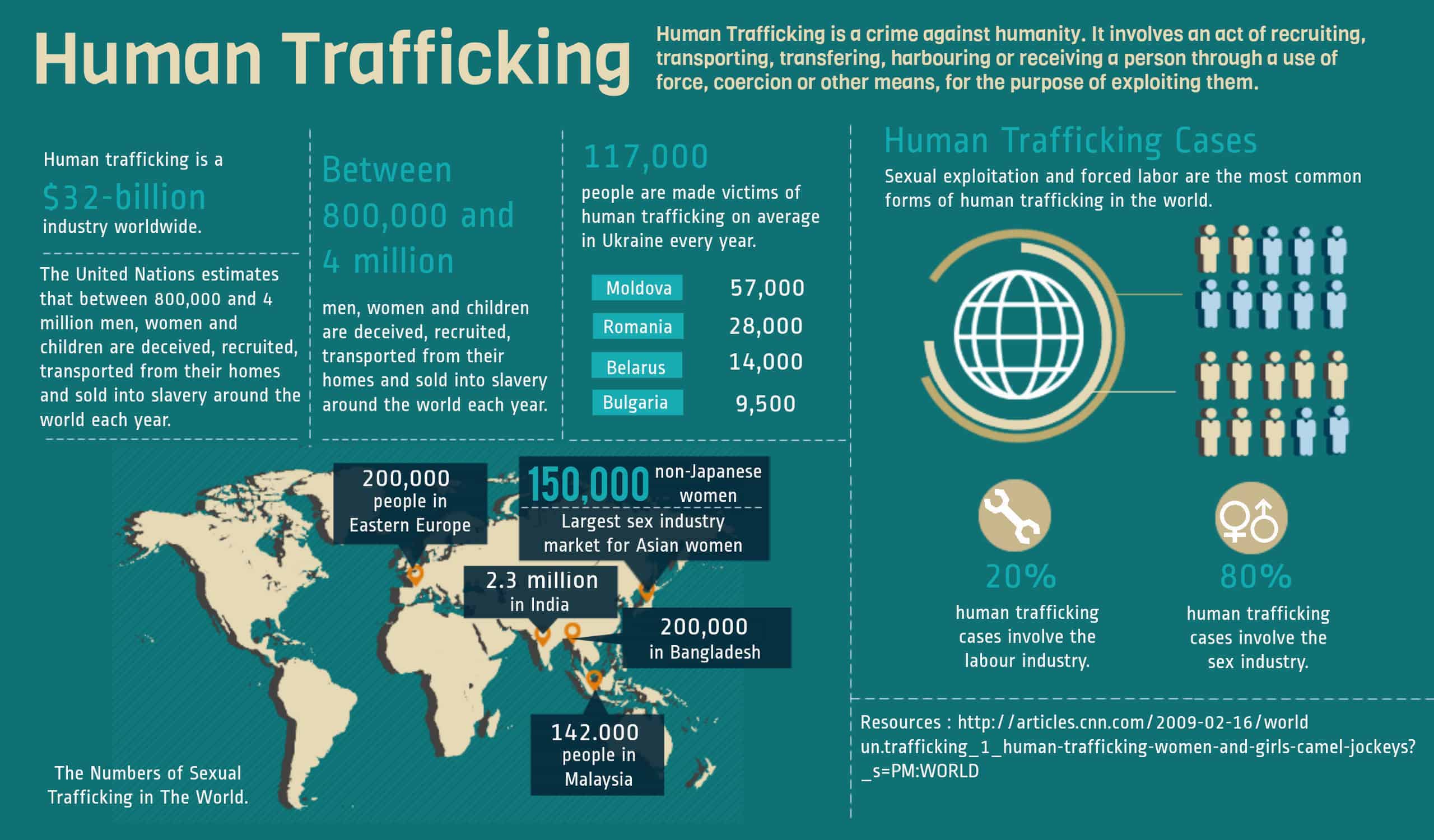

Human trafficking endangers the lives of millions of people around the world, and it is a crime that knows no borders. Trafficking networks operate both domestically and transnationally, and although abuses disproportionally affect women and girls, the victims of this ongoing global tragedy are men, women, and children of all ages. Around the world, we are monitoring the progress of governments in combating trafficking while supporting programs aimed at its eradication. From forced labor and debt bondage to forced commercial sexual exploitation and involuntary domestic servitude, human trafficking leaves no country untouched. With this knowledge, we rededicate ourselves to forging robust international partnerships that strengthen global anti-trafficking efforts, and to confronting traffickers here in the United States.

Trafficking in persons (TIP), or human trafficking, is a widespread form of modern-day slavery. Traffickers target all populations, around the world and right next door: women and men, adults and children, citizens and non-citizens, English speakers and non-English speakers, and people from all socioeconomic groups. Some populations, such as runaway children, undocumented immigrants, the indigent, and people with physical and mental disabilities, are particularly vulnerable to trafficking. Victims are often lured by traffickers with false promises of good jobs and better lives, and then forced to work under brutal and inhumane conditions. Due to the hidden nature of the crime—trafficking victims may work in the open, but the coercion that ensnares them may be more subtle—it is difficult to accurately estimate the number of victims. Despite this challenge, the United States has led the world in the campaign against this terrible crime both at home and overseas.

Profoundly impacting the commercial sexual exploitation of young women and children is the normalization of hypersexualized youth in mainstream American culture. Cultural expectations, norms, and values coupled with interpersonal relationships that support the objectification of women and youth have both shaped and reinforced the sexualization of children at younger ages while simultaneously contributing to youth’s own internalization as sexual objects (American Psychological Association, 2007; Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking, 2010). Concurrently, the media has both contributed to and reflected society’s demand (American Psychological Association, 2007) in a cycle that fosters the inundation of hypersexualized youth in every facet of our culture. Equating youth to beauty and sexual desire has dramatically affected traffickers (i.e. exploiters and purchasers of sex) eagerness to commodify children. Human trafficking does not exist in a vacuum, it is the culmination of cultural, social, political, and economic factors that both influences and sustains the many forms of exploitation.>> Traffickers

Globally, 18.7 million people—90 percent of victims—are exploited by individuals or enterprises in the private sector and 2.2 million people—10 percent of victims—suffer from state imposed circumstances (International Labour Organization, 2015). Men overwhelmingly account for the majority of convicted traffickers worldwide. Roughly 72 percent of convicted traffickers are men and 28 percent are women (UNODC, 2014). In the United States between 2008 and 2010, men comprised 81 percent of suspected human traffickers with 62 percent of sex traffickers identified as Black and 48 percent of labor traffickers identified as Hispanic (Banks & Kyckelhahn, 2011). The identification of Black and Hispanic men as the most prevalent traffickers is a reflection of law enforcement bias. Men and women of all races, ethnicities, and socioeconomic statuses have exploited victims both within and outside of the United States. It is the perception that men of color are more culpable coupled with the policing of low-income communities where people of color are overrepresented that have a profound influence on who is identified and prosecuted as traffickers. According to qualitative data collected in one study of eight major cities in the United States, the most cited factors influencing exploiters entry into sex traffickers were: community influence, familial exposure to sex work (not specified if sex trafficking), dearth of job options, and encouragement from others (e.g. significant others and acquaintances). Exploiters run the gamut from corrupt governments and organized criminal groups, to small networked gang activity and intergenerational and intrafamilial actors of all races, classes, and socioeconomic statuses.

State Imposed >>

Human trafficking is provoked when governments fail to comply with the minimum standards set forth by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime available in the Toolkit to Combat Trafficking in Persons (UNODC, 2006). Human trafficking is provoked not only by governments failing to comply with UNODC's standards but also by a broader range of socio-economic and political factors, such as corruption, lack of law enforcement resources, poverty, gender inequality, and armed conflicts, all of which create fertile ground for trafficking to thrive. Militant rebel groups like the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) is an example of state imposed commercial sexual exploitation. Militant rebel groups like ISIL exploit these vulnerabilities to impose their own twisted agendas, using the commodification of individuals as a means of funding and asserting control. ISIL has been known to conquer villages and commodify non-Muslim women and girls, between the ages of 1 and 50, for sexual purposes (Callimachi, 2015). The heinous acts committed by ISIL highlight the urgent need for international cooperation to counter both state-imposed and non-state actor-driven trafficking. Efforts to combat trafficking are multifaceted and extend beyond dismantling militant groups. Collaborative initiatives between governments, international organizations, and civil society play a pivotal role in addressing the root causes of trafficking, providing protection to victims, and holding perpetrators accountable. While the United States is actively engaged in combating trafficking within its borders, there remains a critical responsibility to address the demand for commercial sexual exploitation that fuels trafficking on a global scale. U.S. citizens have a role to play in this fight as well. Awareness campaigns and education can sensitize individuals to the grave consequences of their actions when they engage in purchasing sex from victims abroad or within the United States. By addressing the demand side of trafficking, citizens can contribute to breaking the cycle and reducing the incentives that drive traffickers to exploit vulnerable individuals. This collaborative effort, involving governments, organizations, and individuals alike, is crucial to eradicating the deeply rooted issue of human trafficking and ensuring the protection and dignity of all people.

Organized Crime and Gangs >>

The intricate web of transnational organized criminal groups poses an alarming threat as they diversify their illicit activities across borders. These groups exhibit a level of sophistication that enables them to simultaneously profit from the trafficking of drugs, persons, and weapons, exploiting vulnerabilities within and between countries. Their ability to exploit unsuspecting victims is exemplified by their adeptness at using legitimate channels, such as valid business and tourist visas, to smuggle individuals into the United States. Once victims arrive, these criminal networks cunningly manipulate their circumstances, confiscating their possessions and coercing them into situations of captivity that extend beyond their visa limitations. The use of falsified documentation further entrenches the victims' vulnerability and dependence on these criminal enterprises. Of grave concern is the role that organized criminal groups play in the perpetuation of sex trafficking, both of foreign-born and native women and girls. This dark nexus of trafficking networks goes beyond forced prostitution and extends to the coerced participation of victims in other criminal activities like the trafficking of drugs and weapons. This multi-pronged approach not only maximizes the criminal organizations' profits but also fuels a cycle of exploitation that entraps victims in an intricate web of criminality. In California, the presence of well-known organized criminal groups with specific ties to human trafficking further amplifies the urgency of this issue. Asian and Eurasian transnational criminal rings have established a significant foothold in both domestic and international human trafficking networks. Notable gangs like Asian Gangsters and Armenian Power exploit the shared ethnic and cultural backgrounds of their victims, perpetuating sex trafficking within communities that should be places of safety and support. Addressing the threat posed by these organized criminal groups demands a coordinated, multi-pronged approach involving law enforcement agencies, governmental bodies, non-governmental organizations, and international cooperation. By dismantling these networks and providing comprehensive support to survivors, it becomes possible to disrupt the intricate chain of exploitation and restore the dignity and rights of those ensnared in these heinous activities.

Family, Guardians, and Peers >>

Among the distressing aspects of child trafficking for commercial sexual exploitation (CSEC) is the disturbing prevalence of familial figures and close companions as coercive traffickers. These individuals, ranging from biological parents and legal guardians to foster parents and even relatives, exploit the profound trust that children naturally place in those closest to them. This horrifying trend initiates children into commercial sexual activity at shockingly young ages, with the exploitation often extending well into their young adulthood, leaving deep scars that persist for years. In a national survey, several law enforcement respondents named parents as prominent traffickers of children in rural areas. In a New York-based study, 47 percent of CSEC were recruited by “friends” both within and outside of their peer network, though it should be noted some of the “friends” acted as surrogate recruiters for traffickers. The initiation by “friends” and peer-to-peer recruitment methods are typically reinforced by peer pressure, society’s glamorization of and the youth’s curiosity about the sex industry, and the youth’s lack of financial resources or economic alternatives. There are unique challenges for populations affected by this recruitment method. It may become difficult for youth to self-identify as a victim of trafficking worthy of appropriate services when commercial sexual activity is normalized within their peer network. Furthermore, the normalization of commercial sex affects how youth desensitize sexuality and internalize their role as sexual objects which ultimately reinforces their reluctance to exit the exploitation and access services. Addressing these challenges requires a multifaceted approach that focuses not only on rescuing and rehabilitating victims but also on societal and systemic change. Education campaigns that emphasize the importance of healthy relationships, consent, and awareness of exploitation can empower young individuals to recognize the warning signs and seek help. Furthermore, providing comprehensive support services that address both the immediate and long-term needs of survivors is crucial for breaking the cycle of exploitation and helping victims reclaim their agency and dignity.

Romeo >>

The “Romeo” style trafficker is often, but not always, gang-affiliated; under the facade of a “boyfriend” this trafficker uses affection, charm, and positive attention throughout the “grooming process” to manipulate girls and young women. The romance and manipulation are underscored by flattery, “acts of love,” and material gifts (e.g. clothes, food, money). The trafficker creates a false sense of security then exploits the victim’s financial and emotional vulnerabilities. The victim typically has feelings of indebtedness for the trafficker’s perceived kindness, which ensures she will initially comply with desires for her to engage in commercial sex acts with his “friends” or strangers. The grooming period can last for hours, months, or years before the trafficker systematically breaks down the victim’s self-esteem, social support systems, and resistance. As the affection and gifts diminish the trafficker then asks, persuades, or forces the victim into exchanging sexual activity for compensation. The victim’s loss of agency over their own body is routinely coupled with physical, emotional, and sexual violence; thus, reinforcing the “boyfriend” dominance and unequal power dynamic and ensuring an omnipotent presence the victim cannot easily detach from. At times, victims become pregnant by their trafficker which can be a manipulative and coercive tactic that reinforces the victim’s dependence, further complicating their ability to exit the exploitation. Typical coercive measures include but are not limited to: gang rape, isolation, torture, beating, cutting, burning, deprivation of basic needs, threats of murder, and “branding” the practice of physically tattooing the trafficker’s moniker on the victim to convey her commodification as his property. The “boyfriend” or “Romeo” trafficker is the most extensively studied and is believed to be the most prevalent type of trafficker.

CEO >>

The “CEO” type trafficker lures girls and young women into commercial sexual exploitation with false promises of work in legitimate business settings. The business guise coupled with the extravagant use of money often deceives aspiring actresses and entertainers into believing they are entering a professional business dynamic. This type of trafficker might operate a legitimate business, be in a network with legitimate businesses, or illegally operate a store-front. Like the “Romeo” trafficker, these traffickers might use “flattery” and “charm” but their tactics are more reliant on their position of authority as talent “agents”. In order to legitimize their claims the “CEO” trafficker often has victims’ complete initial paperwork through which the trafficker gleans personal information while the victims unknowingly sign contracts that consent to performing duties like commercial sex acts. This type of trafficker is the least discussed within available literature, though equally exploitative and opportunistic. Unlike the "Romeo" trafficker who relies on charm and flattery, the "CEO" trafficker wields their perceived authority and promises of professional advancement as a means of control. One of the most insidious aspects of the "CEO" trafficker's tactics lies in their ability to exploit the victims' ignorance about legal matters. By coaxing victims into signing contracts and completing initial paperwork, the traffickers collect personal information while simultaneously obtaining consent for performing duties that often involve engaging in commercial sex acts. This duplicitous maneuver further entraps victims, as they unknowingly provide the traffickers with the tools necessary to exert control and maintain a facade of legality.

Gorilla >>

The "Gorilla" trafficker represents a chilling and particularly violent manifestation of human trafficking, characterized by its absence of any prior relationship or pretense. Operating through a brutal combination of forced kidnapping, physical violence, drug manipulation, and blackmail, these traffickers shatter the lives of their victims without hesitation or remorse (Sowers Education Group, 2014). This type of trafficker preys upon youth indiscriminately, targeting them without any prior engagement or grooming process. A harrowing example involves traffickers strategically lingering near schools and parks, singling out vulnerable youth by their school uniforms and subjecting them to horrifying forced abductions. Although this type of trafficker is less common, it is typically more enduring and abusive than other traffickers. These traffickers use coercion, isolation, and actual or threatened physical violence to ensure that their victims remain fearful and comply. These types of traffickers do not allow victims to look other men in the eye or speak without permission as a way of preserving their sense of power over victims. This situation is the most difficult for victims to escape, as traffickers afford their victims the least amount of agency. The oppressive nature of this trafficking scenario compounds the victims' suffering, making escape an incredibly daunting challenge. The absence of any semblance of relationship or camaraderie with their captors denies victims even the slightest source of empathy or connection. This type of trafficking represents a heart-wrenching reality where victims are subjected to unimaginable abuse and stripped of their humanity, leaving them trapped in a cycle of torment and despair.

>> Statistics and Proxy Sources

Human trafficking is marked as the fastest growing criminal enterprise in the world (Harris, 2014). It is estimated that there are 21 million women, men, girls, boys, and transgender individuals trafficked worldwide this is roughly equivalent to 3 out of every 1,000 people (International Labour Organization, 2015). Each year labor trafficking entraps 14.2 million people and sex trafficking victimizes about 4.5 million people; on a global scale these estimations make forced labor about 3.5 times more prevalent than commercial sexual exploitation (International Labour Organization, 2015). In both capacities women and girls are identified as the most trafficked populations, comprising 11.4 million of the labor and sex trafficked victims (International Labour Organization, 2015). Adults account for 74 percent—15.4 million—of victims and children younger than 18 years old are 26 percent—5.5 million—of victims (International Labour Organization, 2015). According to data collected by the International Labour Organization (ILO), exploitation occurs in a myriad of settings but the most notable and widespread industries are domestic servitude, agriculture, construction, manufacturing, and entertainment (2015). Although ILO is often cited by anti-human trafficking activists worldwide, there are critics to these and a majority of other available statistics. Unfortunately, much of the circulated quantitative data cannot act as an accurate representative sample of human trafficking victims in the United States or abroad. Estimates are typically followed by caveats and qualifying statements with researchers urging readers to refrain from republishing estimates without acknowledging limitations (IOM & NRC, 2013).

In the United States, the commercial sexual exploitation of women and girls has been the most recorded type of human trafficking. Domestically, the most at-risk populations tend to be society’s most marginalized and vulnerable groups: women, children, and adolescents. Well-known antecedents and characteristics of victimized minors include: missing, runaway, thrownaway (i.e. asked or forced to leave home), homeless; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered, or questioning (LGBTQ); gender non-conforming (GNC); minorities and girls of color especially African-American; migrant workers; Native Americans especially girls; cognitive and developmental delays; child welfare involvement; juvenile justice system involvement; history of neglect and abuse, especially child sexual abuse; exposure to domestic violence; history of exploitation in community or family; lack of care or basic needs (e.g. food, clothing); youth or caregivers with alcohol or substance dependency; truancy; disconnection from the education system; and poverty (Human Rights Project for Girls, 2015; IOM & NRC, 2013; U.S. Department of State, 2014; Walker, 2013; Walker & Quraishi, 2014). Additionally, the advent of relatively anonymous and accessible technology like Internet-based chat rooms, social media platforms, and apps with built-in GPS have made it easier than ever for predators to locate, communicate with, and entrap unsuspecting victims (Webb, “What the Tech?,” 2016).

>> The War Against Human Trafficking

This 2019 documentary tells the stories of young women coerced into prostitution – and follows one police unit that’s committed to rooting out sexual exploitation. Award-winning director Jezza Neumann and producer Lauren Mucciolo (“Poor Kids”) embed with the Phoenix police unit that’s tackling child sexual exploitation, offering an inside look at the lucrative industry through unique access to a series of undercover, high-stakes police operations. They also film with young women who have escaped the trade. Using fake online ads as decoys, the Phoenix police unit targets both the traffickers luring young women into prostitution, and the “buyers” – many of whom claim to not know that the girls they interact with are victims of trafficking. With extensive and intimate access to local law enforcement, prosecutors, service providers and the women themselves, the film shines a light on the hidden reality of sex trafficking in America.

Human trafficking can occur in close proximity to a victim’s place of origin or residence as evidenced by children born into servitude and exploitation perpetrated by legal guardians, relatives, and friends. There is an important distinction between human trafficking and human smuggling in that the former is centered on exploitation while the latter focuses on the transportation of individuals evading country-specific immigration laws (U.S. Department of State, 2006). Although distinct from each other, trafficking and smuggling are not mutually exclusive. The two can, and do, overlap when individuals who are initially smuggled by their own will lose their autonomy in a captive state (e.g. debt bondage) (Human Smuggling and Trafficking Center, 2006). The means of trafficking is through the use of force, fraud, or coercion with exceptions for commercially sexually exploited children (CSEC). Sex and labor trafficked adults and labor trafficked minors must provide evidence of force, fraud, and coercion (Freedom Network USA, 2012) in order to be legally considered a trafficking victim and receive related services. Because minors are below the legal age of sexual consent, all minors who engage in commercial sexual activity are victims of sex trafficking and child sexual abuse, not voluntary sex workers or prostitutes, whether or not force, coercion or fraud are present (Finkelhor & Ormrod, 2004; Saar, Epstein, Rosenthal, & Vafa, 2013; Walker, 2013).

Still, force, fraud and coercion are typically involved in the exploitation of minors. Force is a regular occurrence in all types of human trafficking. Sex trafficked victims are often brutalized with high instances of physical, emotional, and sexual violence like rape, torture, and imprisonment (Richard, 2000). Coercion and fraud are often conveyed through psychological manipulation, which may include continuous threats to harm the victim and their family, false deceptions of love and familial-like relationships, and promises to fair wages in legitimate work settings (Office of Refugee Resettlement, 2012). The purpose of trafficking is the exploitation of an individual in exchange for something of value (e.g. money, food, clothing, shelter). TVPA 2000 set a legal framework for local, state, and federal government agencies, law enforcement, prosecutors, and stakeholders to conceptualize and combat trafficking in person. Due to incomplete data on the CSEC population most estimates rely on proxy sources like information on missing, runaway, and homeless youth. Runaway and homeless youth have been highly targeted by traffickers due in large part to the pronounced vulnerabilities of age, inconsistent adult supervision, and lack of protection (National Alliance to End Homelessness, 2011; Walker, 2013). According to the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, it is estimated that in the United States about 1.6 million youth run away from home every year (National Runaway Safeline). Forty-eight percent of children accessing the National Runaway Safeline (NRS) hotline reported abuse and family dynamics (e.g. divorce, problems with siblings or family rules, etc.) as the most common reason. The average NRS caller demographic is female age 16 years old (National Runaway Safeline), though children of all backgrounds, sexes, and socio-economic status are at-risk for running away. Some research estimates that between 30 percent and 50 percent of homeless youth are sex trafficked with no gender bias (Curtis, Terry, Dank, Dombrowski, & Khan, 2008). Youth who are more frequently homeless for longer periods of time are more at-risk for commercial sexual exploitation (National Alliance to End Homelessness, 2011)

Two of the most commonly cited CSEC statistics are largely outdated and lack a strong basis in empirical research methodology. In 2001, a study focused on North America estimated that in the United States between 100,000 and 300,000 youth are at-risk for sexual exploitation each year (Estes & Weiner). This estimate relies on data from various organizations, law enforcement agencies, and human service professionals who serve and track runaway youth statistics. Well-known and highly credible organizations like the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) have encouraged the use of the conservative estimate of 100,000 domestic born-children recognizing it as “empirically sound and defensible” (Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking, 2010). The average age youth enter into sex trafficking is another commonly cited statistic from the Estes and Weiner publication (2001). The report found that girls typically enter sex trafficking between 12 and 14 years old while boys enter slightly younger between 11 and 13 years old (Estes & Weiner, 2001). Multiple reports and anecdotal evidence confirms that youth are trafficked at very young ages. During the 2015 Operation Cross Country, an annual human trafficking raid, the FBI recovered 149 victims, the youngest was 12 years old (FBI, 2015). Between 2012 and 2015, the youngest client served at Saving Innocence, a Los Angeles-based anti-sex trafficking nonprofit organization, was 11 years old though two of their clients entered sex trafficking at 10 years old.

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) is a clearinghouse for information on missing and exploited youth; the organization is a trusted source for data on the overlap of missing children and commercial sexual exploitation (2016). NCMEC data shows a steady increase in the sex trafficking of missing and runaway youth. In 2015, 1 in 5 of the reported 11,800 runaway youth were likely sex trafficked and 74 percent were in foster care or the custody of social services at the time of exploitation. In previous years the organization reported that 1 in 6 runaway youth (2014) an increase from 1 in 7 runaway youth (2013) were likely sex trafficked with about 70 percent of the population in foster care or social service custody when running away (National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, 2016). Statistical information provided by NCMEC shows the value of data from multiple systems (e.g. child welfare and homeless and runaway), in addition to underscoring the need to assess systemic issues that allow children to fall through the cracks at such alarming rates.

Across the nation, there is a pervasive correlation between the child welfare system and CSEC, especially for children of color who are disproportionately represented in the system. In Fiscal Year (FY) 2013 there was an estimated 402,378 children in foster care; FY 2013 and FY 2014, 24 percent identified as African-American or Black and 22 percent identified as Hispanic (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2015b; United States, 2015). African-American girls disproportionately experience compounding and interplaying risk factors like poverty, community and family instability, history in foster care and/or child protective services that undergird their vulnerability to sex trafficking (Human Rights Project for Girls, 2015). Hispanic girls appear to share a similar experience to their African-American counterparts.

It is estimated that anywhere between 50 percent and 98 percent of identified CSEC across the nation have a history in the child welfare system (Walker & Quraishi, 2014). During the 2013 Operation Cross Country, the FBI recovered sex trafficked youth from over 70 cities of which 60 percent were placed in foster care or group homes during the exploitation (Human Rights Project for Girls, 2015). In 2012, 98 percent (86 of 88 youth) of Connecticut’s CSEC population was not only system-involved but had the highest instances of reported abuse while in residential treatment or foster care (Human Rights Project for Girls, 2015).

Traffickers recruit the most vulnerable youth with histories of abuse and neglect as they commonly prey on insecurities and capitalize on gaps in supervision (Walker, 2013; Walker & Quraishi, 2014). Placing youth in multiple foster care settings like group homes exacerbates their risk for further abuse (Bounds, Julion, & Delaney, 2015) due to the lack of consistent oversight and familial attachments, interactions with a multitude of people including traffickers, and an overall instability in care (Saar, Epstein, Rosenthal, & Vafa, 2013; Walker, 2013). System-involved youth who are dissatisfied or unsafe in their placement, wrongly placed in detention centers or homes they once ran from, or frequently run from foster care are at heightened risk for victimization (Bounds, Julion, & Delaney, 2015; Kotrla, 2010). This data conveys the profoundly detrimental factors that inadvertently put youth in the child welfare system significantly more at-risk for commercial sexual exploitation than non-system involved youth.

The complex challenges faced by sex trafficked victims within the child welfare system often lead to a distressing cycle of interaction with multiple parallel systems. The criminalization of these victims perpetuates their vulnerability, resulting in frequent overlap between the child welfare and juvenile justice systems, creating what is known as a dual-system status. Shockingly, girls constitute a significant proportion—ranging from one-third to one-half—of this dual-system population, underscoring the gendered dimensions of this issue (Saar, Epstein, Rosenthal, & Vafa, 2013). Disturbingly, the most vulnerable among these victims may find themselves involved in not just two, but three separate systems: child welfare, juvenile justice, and mental health. A study has revealed that youth caught in the overlap of these three systems experience a significantly higher number of unmet needs compared to their counterparts who are involved in only one system (Bounds, Julion, & Delaney, 2015). This demonstrates the intricate web of challenges that these young individuals navigate, often leading to unaddressed needs and compounding their vulnerability to further exploitation and harm. Efforts to address the intersection of child welfare, juvenile justice, and mental health systems must extend beyond reactive measures and delve into proactive strategies that prioritize the well-being and potential of these young individuals. Recognizing the complexities they face, it's essential to establish coordinated initiatives that target the root causes of their involvement in multiple systems.

The concerning statistics regarding the intersection of child welfare and commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) highlight the deeply rooted vulnerabilities within the system. Research suggests that a staggering proportion of identified CSEC victims have a history within the child welfare system, with estimates ranging from 50 percent to an alarming 98 percent (Walker & Quraishi, 2014). The scope of this issue was evident during the 2013 Operation Cross Country, conducted by the FBI, where over 60 percent of the sex trafficked youth recovered from more than 70 cities were found to have been placed in foster care or group homes while being exploited (Human Rights Project for Girls, 2015). A particularly distressing example emerges from Connecticut in 2012, where a shocking 98 percent of the state's CSEC population (86 out of 88 youth) had not only been system-involved but also experienced the highest instances of reported abuse while in residential treatment or foster care (Human Rights Project for Girls, 2015). This staggering statistic not only underscores the systemic shortcomings that perpetuate vulnerability but also reveals the extent of the harm that can occur within environments intended to provide care and protection.

Throughout the country CSEC victims, especially girls of color and LGBTQ/GNC youth, intersect with the juvenile justice system at alarming rates on non-violent offenses like prostitution and related charges. Nationally, girls represent one-fifth to one-quarter of the juvenile justice population with an overrepresentation of girls of color (Saar, Epstein, Rosenthal, & Vafa, 2013). The overrepresentation of girls of color is evidenced by their rates in residential treatment placements per capita, especially in comparison to Caucasian girls: Native American girls (about 1 percent of the general population) are in placements at a rate of 179 per 100,000; African-American girls (about 14 percent of the general population) at 123 per 100,000; Hispanic at 47 per 100,000; while non-Hispanic Caucasian girls are detained at the rate of 37 per 100,000 (Saar, Epstein, Rosenthal, & Vafa, 2013). The LGBTQ population continues to be overrepresented in the juvenile justice system. In a study of 1,400 system-involved girls across seven jurisdictions 40 percent of the sample identified as LGBTQ/GNC in comparison to 14 percent of boys who identified as LGBTQ (Saar, Epstein, Rosenthal, & Vafa, 2013). Each year more than 1,000 CSEC victims are detained and charged with prostitution and related offenses (Human Rights Project for Girls, 2015). Though it is likely that a significant number of CSEC victims go unidentified in the juvenile justice system across the nation. The prevalence of CSEC girls of color detained on non-violent crimes like prostitution charges reinforces the stigma that this population is worthy of criminalization (Houston, 2015) rather than rehabilitative services or addressing systemic issues that lead to the victimization of this population.

Sex trafficking is one of the most misunderstood criminal enterprises in the US. In popular belief; women are forced across borders and held against their will. But a new picture shows eight in ten victims are US citizens. Many are enslaved through drugs and like old-world slavery, are branded as property. Often confused as valid sex workers, Columbus, Ohio is helping to free victims and transform their marks of "ownership". Reporter: Elaine Jung. Premiered 7 December 2019 on BBC.

An overwhelming amount of sex trafficked and criminal or juvenile justice system involved women and girls have experienced multiple forms of exploitation on the sexual abuse continuum. In 2006, an Oregon-based juvenile justice system study reported that 93 percent of the girls sampled had a history of sexual or physical abuse (Saar, Epstein, Rosenthal, & Vafa, 2013). Prior to reaching 13 years old, 75 percent of the sample experienced at least one incident of sexual abuse and 63 percent experienced both sexual and physical abuse (Saar, Epstein, Rosenthal, & Vafa, 2013). Childhood sexual abuse is the most commonly identified antecedent to commercial sexual exploitation and sexual victimization (Bounds, Julion, & Delaney, 2015; Friedman & Willis, 2013; Walker, 2013). This risk factor interplays with multiple domains including the child welfare, mental health, and juvenile justice systems (Bounds, Julion, & Delaney, 2015). Sexual abuse contributes to sexual desensitization and an inability to determine healthy boundaries and relationships (Bounds, Julion, & Delaney, 2015). According to Administration for Children, Youth and Families (ACYF), between 70 percent and 90 percent of CSEC have a history of child sexual abuse, physical abuse, neglect, and/or trauma (2013). In one Oregon-based study of CSEC survivors, 85 percent had a history of incest (Walker, 2013). Child sexual abuse can result in anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, wide-ranging emotional and physical issues, and problems developing healthy interpersonal relationships (Kramer & Berg, 2003). Children with a history of sexual abuse are more likely to be involved in dating violence, experience rape, and are at a higher risk for sex trafficking (ACYF, 2013). Furthermore, in their lifetime these children are 28 times more likely to be detained on “prostitution charges” than their non-sexually abused counterparts (ACYF, 2013). These statistics do not represent the full breadth of trafficked victims but they provide insight into risk factors that put target populations at greater risk for multi- layered complex trauma and ongoing abuse from childhood into adulthood.

Enacted in 2014, the Preventing Sex Trafficking and Strengthening Families Act directly addresses prevention and intervention of CSEC involved in the foster care system, enhances adoption incentives, and aims to improve international child support recovery. By law, states are now required to identify, report, and determine appropriate services for youth who are at-risk for or confirmed victims of sex trafficking. The policy requires the child welfare system to input CSEC data in the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS). AFCARS will then quantify CSEC in their annual reports. The child welfare system is also required to locate and respond to youth who run away from foster care placement within 24 hours; the protocol requires the child welfare system to notify local law enforcement and NCMEC to ensure appropriate measures are taken to identify and recover the children. This will assist in addressing and accounting for the pervasive problem of children running away from placement, an issue CSEC survivors and service providers continuously struggle with during the reintegration process. Operated by Polaris, the National Human Trafficking Resource Center (NHTRC) provides 24-hour confidential support in over 200 languages to survivors, community members, and stakeholders who contact the hotline. All incoming human trafficking tips are synthesized into annual reports specific to geographic regions; this fulfills the organization’s objective of identifying trends across the United States (Polaris Project, 2013). The annual reports provide information related to geographic regions, victim demographics, types of venues-involved, and types of callers; in addition to detailing the impact of human trafficking on those who are exploited (NHTRC, 2014; Polaris, 2015). From January 2007 through June 2015, the hotline received a total of 103,026 signals: 91,405 phone calls; 5,307 online tips; and 6,674 emails (NHTRC, 2015). This data underscores the hotlines significance in providing services to callers, directing information to local authorities, and collecting human trafficking data. In 2014, the hotline received 24,062 signals nationwide: 21,431 phone calls; 1,482 online tips; and 1,149 emails (NHTRC, 2014). Community members tend to be the most common type of caller, undergirding the importance of community awareness, adequate education, and involvement. In 2015, trafficking victims were the second highest callers at 16 percent; the majority of callers, about 24 percent, found the hotline through an Internet-based search. The collected data relies on awareness of how to first identify human trafficking and then report the incidents. NHTRC reports serve an important function of highlighting high-intensity areas but cannot be taken as a true depiction of national statistics.

>> Sex Trafficking of Minors

Sex trafficking of domestic-born female minors has been at the forefront of anti-human trafficking discourse as research suggests that domestic youth are the most vulnerable to victimization in the United States (Kotrla, 2010). The most documented type of child trafficking is commercial sex; other types of prominent commercial sexual exploitation often intersect like the production of child pornography, exotic and nude dancing, and live sex shows though they tend to receive less attention and remain underreported (Cole, Sprang, Lee, & Cohen, 2014; Hughes, 2005; Reid, 2011).

In the United States, sex trafficking of domestic-born minors is noted as the most common form of human trafficking that victimizes citizens (National Alliance to End Homelessness, 2011). Although CSEC data is more readily available than information on sex trafficked adults and labor trafficked minors and adults, there are still shortcomings in existing literature that do not capture the full scope or scale. Reputable sources like Polaris Project have encouraged comprehensive and methodical research that more accurately quantifies the number of trafficked victims. Polaris explains, “...the trafficking field has to rely on incomplete and imperfect data drawn from small data sets” (2015a). Many stakeholders continue to reference and republish outdated and incomplete statistics at times knowing the credibility and generalizability is questionable because of the statistical dearth that exists. Other sources like the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and National Research Council (NRC) recognize the extreme difficulty of collecting prevalence data with this type of crime and encourage specialized research that focuses on specific vulnerable populations (e.g. LGBTQ, systems-involved, etc.) (2013).

>> From Foster Care to Trafficking: An Analysis of Contributory Factors

The practice of child sex trafficking – more properly known as the commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) – is nothing new. In all likelihood, it is as old as commerce itself. However, in recent decades the business of CSEC has grown at a staggering rate, burgeoning into a massive industry due primarily to two related phenomena: globalism and the rise of the Internet. While the actual numbers are subject to debate, common estimates place the total number of sex-trafficked individuals (adults and children) in the hundreds of thousands in the U.S. alone. Globally, those numbers are likely in the millions, fueling an industry that may generate as much as $32 billion annually. The appeal for criminals is obvious, as much as it is horrific: sex trafficking provides them with a renewable resource. Whereas drugs are only consumed once, a human being can be sold over and over again. But humans, of course, can’t simply be manufactured. Professional traffickers rely on complex forms of psychological manipulation to lure their victims and maintain a hold over them. They are skilled and resourceful, and they know where and how to find vulnerable victims. In the US, that often means preying on children involved in the child welfare system.

The linkages between CSEC and the child welfare system – in particular, foster care – have grown more obvious in recent years thanks to statistics from the criminal justice sphere. The FBI reported in 2013 that 60% of children recovered from CSEC incidents had previously been in out-of-family care. A 2014 Department of Justice report estimated that 85% of girls involved in CSEC were previously involved in the child welfare system. In 2015, California Attorney General Kamala Harris reported that 59% of children arrested on prostitution-related charges in Los Angeles County had previously been in foster care. The Connecticut Department of Children and Families reported that 86 out of the 88 children identified as CSEC victims had been involved with child welfare services. And in 2007, the city of New York reported that 75% of identified victims of CSEC had experienced some contact with the child welfare system.

Anaiah Walker was 15 when she went missing from Arizona’s foster

care system in December 2019. Five months later, her body – shoeless

and disfigured – was found discarded on the median of a freeway.

It took the police 12 days to identify the child.

Anaiah was one of the estimated 20,000 children who go missing

from the child protection system every year. State agencies weren’t

required to report missing foster children to law enforcement until

2014. Since then, reports of children missing from care have more

than doubled. Protocols and best practices for the search and

recovery of missing foster children are scarce, and laws outlining

search requirements are virtually nonexistent.

Traffickers know that children without stable families are easy

prey. Research overwhelmingly shows that most sexually trafficked

children are from foster care. Some children, like Anaiah, are found

dead. Some are never found.

"No one looks for us. I really want to make this clear. No one looks for us." -T. Ortiz Walker Pettigrew

>The Psychology of Monetization

The compensation system for foster parents introduces complex ethical considerations that intertwine with the well-being of vulnerable children. Although foster parents receive payment for their caregiving role, the situation becomes more convoluted when documentation indicating severe emotional or behavioral disturbances is incentivized, potentially leading to higher stipends. While these financial incentives are intended to support the child's needs, the lack of a monitoring system in most states raises questions about the proper allocation of these funds.As awareness grows, it becomes increasingly evident that this compensation structure can inadvertently perpetuate feelings of objectification and worth tied to financial considerations in children under foster care. This reality is particularly poignant for foster children, especially adolescents, who grasp the financial dynamics of their situation. Many are well aware that their caregivers are being paid to care for them and, unsettlingly, some even know the exact dollar amount involved. Commonly heard expressions from these children underscore the distressing impact of this awareness, such as "I feel like I'm only worth a paycheck to these people," or "They act like they care about me because they're being paid to," and a prevailing sentiment being "They receive money on my account, but they prioritize spending it on themselves rather than on my needs."

The shadow of monetization looms large over discussions about foster care, presenting a formidable challenge that often remains unaddressed. Beyond its immediate implications, this issue possesses a subtle yet potent connection to the intricate journey from foster care to trafficking. Dr. Mallon's insight, shared in a personal conversation with the author on February 28, 2018, encapsulates this connection succinctly: "Foster care and trafficking are similar. People are paid to take care of you, and they promise to offer protection to you in exchange for something. This sentiment reverberates powerfully through the poignant account of a survivor, featured in the O. L. Pathy Foundation report. Her narrative exposes the disconcerting parallels between her experiences in the foster care system and the sinister realm of commercial sexual exploitation. She articulates how the tumultuous environment of foster care, marked by sudden dislocations and a lack of control, ingrained the belief that care and protection were only attainable through monetary exchange. Tragically, this distorted perception was skillfully exploited by her trafficker, who manipulated her into believing that her role in the exploitative "family" structure was tied to generating income.

This survivor's harrowing journey underscores the profound impact of financial dynamics on vulnerability, shedding light on the unintentional ways in which the monetization of care can contribute to the perpetuation of trafficking. Confronting this reality requires a shift in focus – a transition from financial incentives to genuine emotional support. One survivor, quoted in the O. L. Pathy Foundation report, explicitly expresses this:

Being in foster care was the perfect training for commercial sexual exploitation. I was used to being moved without warning, without any say, not knowing where I was going or whether I was allowed to pack my clothes. After years in foster care, I didn’t think anyone would want to take care of me unless they were paid. So, when my pimp expected me to make money to support ‘the family,’ it made sense to me.

The complex dynamics surrounding foster care further reveal the problematic intersection of financial incentives and the well-being of vulnerable children. While foster parents are compensated for their caregiving efforts, the system's design and lack of transparency can inadvertently create an environment where the child's worth is tied to monetary considerations. This distressing reality is exacerbated by the fact that foster parents often receive higher stipends for children with severe emotional or behavioral issues. However, many states lack mechanisms to monitor how these funds are spent, leaving room for misuse.

As foster children become aware of these financial aspects, they may experience a deep sense of objectification and commodification. They recognize that their value is being measured in terms of the stipends their foster parents receive, potentially leading to feelings of being monetized rather than genuinely cared for. Adolescents, in particular, often become cognizant of the exact dollar amounts associated with their presence in the foster home. This unsettling realization can manifest in statements like "I'm worth nothing but a paycheck to these people," exposing the profound psychological impact of this monetization.

The troubling connection between foster care and human trafficking becomes evident when considering the parallels between promises of protection and care. Survivors' testimonials echo this sentiment, as they draw striking comparisons between the foster care system's dynamics and the manipulative tactics used by traffickers. This overlap, characterized by individuals being moved without consent and reliance on external caregivers for survival, underscores the vulnerabilities that can be exploited by traffickers. One survivor's poignant account illustrates the correlation: her experiences in foster care, marked by unpredictability and dependence, conditioned her to believe that care was contingent on financial incentives. Consequently, this perspective aligned with the demands of her trafficker, mirroring a pattern of exploitation in which she had tragically grown accustomed.

These Little Ones (documentary)

Confronting this issue demands a comprehensive examination of the foster care system, coupled with measures to prioritize the well-being and agency of foster children. Transparency in financial transactions, rigorous monitoring of caregiving environments, and a focus on nurturing genuine connections are vital steps toward dismantling the monetization dynamic. By addressing this issue head-on, society can strive to restore dignity and value to foster children, creating an environment where their worth is determined by their intrinsic humanity rather than monetary considerations.

Additionally, the monetization issue within foster care underscores the urgency of comprehensive reform to prioritize the holistic well-being of children in the system. It's imperative to shift the narrative away from monetary incentives and refocus on the emotional, psychological, and developmental needs of these vulnerable individuals.

Implementing safeguards to ensure that funds allocated for foster children are indeed used for their benefit is a critical step forward. Establishing a transparent tracking system that monitors how stipends are being spent could help prevent potential misuse and promote accountability. Moreover, fostering open communication between foster parents, caseworkers, and the children themselves can facilitate an environment where financial aspects are transparently discussed, allowing for a healthier perspective on care and support.

Equally important is the provision of specialized training for foster parents to enhance their understanding of the psychological impact of the system's dynamics on children. Empowering caregivers with the tools to provide not only material support but also emotional security can create a more nurturing environment. Moreover, fostering a sense of agency and self-worth in foster children can counteract the feelings of objectification that stem from monetary associations.

Addressing the monetization issue in foster care is not only about improving the lives of these children within the system but also about mitigating potential vulnerabilities that could be exploited by traffickers. By prioritizing children's emotional well-being and dignity, society can make significant strides in preventing the cycle of exploitation and fostering an environment where every child feels valued for who they are, not for financial gain. This multifaceted approach requires collaboration among policymakers, child welfare professionals, advocacy groups, and foster parents themselves, in order to build a foster care system that genuinely serves the best interests of the children it aims to protect and nurture.

This investigation has uncovered few substantial articles, and only one example of scholarly research: the UMass Lowell “Pathways to Trafficking” project, which was conducted in collaboration with the U.S. Department of Justice. The most substantial summation of existing information is a report from the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers entitled, "Trafficking and the Child Welfare System Link: An Analysis". Beyond this, coverage of the foster care-trafficking linkage has been primarily limited to the popular press, including the 2014 Huffington Post piece that coined the phrase “the Foster Care to Child Trafficking Pipeline”. Many of the articles cited in this report attest to the fact that substantially more research is needed, to better understand the association, identity specific associated factors, and to serve as the basis for public policy. One positive example of such policy change was the 2014 Preventing Sex Trafficking and Strengthening Families Act (PSTSFA). Dave Reichert (R-WA), the sponsor of PSTSFA, was a vocal critic of the child welfare system, and explicit in his belief that foster care makes children more vulnerable to being trafficked. The law seeks to address this by patching key gaps in the system, particularly in areas of data collection and the reporting of missing children to NCMEC, with an emphasis on youth who have run from care or who have a prior history with CSEC. The full impact of this law – which gradually rolls out incremental changes to a massively problematic system – has yet to be evaluated

In 2013, the O. L. Pathy Family Foundation published “An Unholy Alliance,” which presented prior data from law enforcement that evidenced the foster care-trafficking linkage and speculated as to the causal factors. Lillie’s article identifies four common factors in the childhood experiences of survivors – prior sexual abuse by a family member, parental neglect or abandonment, time spent as a runaway or throwaway, and homelessness from aging out of foster care – and connects each of these to deficiencies in the foster care system. In 2015, the West Virginia Law Review published “The Civil Rights of Sexually Exploited Youth in Foster Care” which gathered existing data on the topic, noting serious gaps in the academic research. The report ultimately provided support for PSTSFA while denouncing the lack of accountability foster parents face when children are sexually exploited while under their care. In 2016, the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers published the extremely thorough “Trafficking and the Child Welfare System Link: An Analysis,” which presented the newest law enforcement data, information about the 2014 law, and excerpts from survivor testimony.

The Pathways Project, cited frequently in this report, was conducted in 2009 by the University of Massachusetts Lowell.34 “Pathways into and out of commercial sexual victimization of children” presents extensive self-reporting from survivors, with negative foster care experiences and homelessness via aging-out emerging as common themes. A 2017 study published in the Journal of Child Sexual Abuse mentions the foster care- trafficking link explicitly. “Baseline Characteristics of Dependent Youth Who Have Been Commercially Sexually Exploited” presents data on the demographic characteristics, trauma history, mental and behavioral health needs, physical health needs, and strengths of commercially sexually exploited youth involved in the child welfare system in Florida. The study notes the unique vulnerability of children in foster care due to their “unmet needs for family relationships” and their history of trauma

Documentary "CPS Corruption & Pizzagate" by fullysourced

Anaiah Walker was 15 when she went missing from Arizona’s foster care system in December 2019. Five months later, her body – shoeless and disfigured – was found discarded on the median of a freeway. It took the police 12 days to identify the child. Anaiah was one of the estimated 20,000 children who go missing from the child protection system every year. State agencies weren’t required to report missing foster children to law enforcement until 2014. Since then, reports of children missing from care have more than doubled. Protocols and best practices for the search and recovery of missing foster children are scarce, and laws outlining search requirements are virtually nonexistent. Traffickers know that children without stable families are easy prey. Research overwhelmingly shows that most sexually trafficked children are from foster care. Some children, like Anaiah, are found dead. Some are never found.

Writing for Newsweek, Michael Dolce, Of Counsel at the law firm Cohen Milstein, recently summed up the statistical relationship of foster care to sexual abuse of minors:

"Most people don’t know about our nation’s foster care to sex trafficking pipeline, but the facts are sobering. The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) found that “of the more than 18,500 endangered runaways reported to NCMEC in 2016, one in six were likely victims of child sex trafficking. Of those, 86 percent were in the care of social services when they went missing.

The outcomes of law enforcement efforts against sex traffickers repeatedly support the NCMEC estimate. In a 2013 FBI 70-city nationwide raid, 60 percent of the victims came from foster care or group homes. In 2014, New York authorities estimated that 85 percent of sex trafficking victims were previously in the child welfare system.In 2012, Connecticut police rescued 88 children from sex trafficking; 86 were from the child welfare system. And even more alarming: the FBI discovered in a 2014 nationwide raid that many foster children rescued from sex traffickers, including children as young as 11, were never reported missing by child welfare authorities.” [Source]

This is no secret to either the media or the government, yet for some reason the media is for the most part silent about what is happening to children who end up in foster care. News like this is actually click-worthy and profitable for mainstream media, as it fits right into the bad-news-fear-news paradigm, but the lack of attention on this from politicians is also telling, suggesting a willful cover-up.

In 2013, Malika Saada Saar wrote for an article for the Huffington Post describing the same scenario. Victims of child sex trafficking overwhelmingly come from the foster care system, and the nature of their psychological development in this environment makes them perfect sex slaves, for they tend to become acculturated to this abuse and see themselves as worthless except for sexual abuse. Again, Dolce comments from his perspective in the legal field working directly with victims of this type of abuse.

"Children are learning all the time, and in abusive foster or group homes they learn that their worth as humans is not intrinsic. Their worth is what the abusive caregiver gets from them, whether simply a paycheck from the state or their bodies for sex, as happened to some of my clients.This conditions them to be subservient to pimps—giving all they have in exchange for essential needs, like food and shelter. As one of my clients put it, after extensive physical and sexual abuse in state care, the day she turned 18 and left the system with no community support, job or money, she saw herself in one way: “There was a gold mine between my legs.” [Source]

Documentary "Save the Babies" by Patrick Howley and Ben DeLaurentis

The hardest part about the times that we live in, is that the real villains of the world, more than likely in a position of power, work constantly to manipulate your perception. They think ten moves ahead in order to make you doubt the obvious before it is even presented. Child trafficking is a perfect example. This is the real epidemic, and all the numbers are there, and it’s truly frightening when you realize just how serious it is.

- Every two minutes, a child is exploited in the sex industry.

- According to USA Today, adults purchase children for sex at least 2.5 million times a year in the United States.

- 300,000 children in the United States are victims of child sex trafficking every year.

- It is estimated that there are 100,000 to 150,000 under-aged child sex workers in the U.S. These girls aren’t volunteering to be sex slaves. They’re being lured — in most cases, they have no choice.

- This is a highly profitable, highly organized and highly sophisticated sex trafficking business that operates in towns large and small, raking in upwards of $9.5 billion a year in the U.S. alone by abducting and selling children for sex.

- The child sex trafficking industry reportedly makes more money than the NFL.

- 2 million children are victims of child sex trafficking each year across the globe.

Ironclad: Change Agents with Andy Stumpf - Ep. 1 | Hunting Sex Traffickers (with Glenn Devitt)

Glenn Devitt is an Army veteran, a former member of the Department of Homeland Security's H.E.R.O. (Human Exploitation Rescue Operative) program, and the CEO of the Sentinel Foundation. The organization exists for a single reason: to end underage children being exploited around the world. Today on Change Agents, Glenn and Andy Stumpf discuss Glenn's background, the origins of the Sentinel Foundations, the reality of child exploitation, and how Change Agents listeners can get involved in the fight.

Documentary "Pedogate 2020 PT.II - Tom Hanx" by MouthyBuddha

Families Resist / Stop CPS Corruption Rally at the California State Capitol

The family policing system in the United States, aka Child Protective Services or CPS, has waged war on the American family. Black, Indigenous, and Poor families are especially vulnerable and as such are overrepresented in the system. Nationwide, black children account for only 14% of the population but represent nearly 25% of all CPS cases. Meanwhile, about half of all indigenous children will experience a child welfare investigation before they turn 18. And finally, since poverty is conflated with neglect and parental unfitness by the “child protection” system, poverty is the single most important predictor of placement in foster care and the amount of time spent there.

Moreover, the system lacks accountability, transparency, and oversight. Families are all too often unnecessarily destroyed and children are frequently placed in foster and group homes where conditions are worse than in the homes they were removed from. It is incredibly traumatizing to remove a child from everything they have ever known or loved. There is no reason why a family should be destroyed. Children should be protected and supported by the government by providing services to keep families together instead of assuming parents inability to care.

This must end. The time is now to come together and RESIST together, and to demand real and lasting change. Children deserve better and families belong together.

Assembly Member Isaac Bryan will be one of the speakers at the Rally!!!!

----------

As of October 1, 2021, there are 58,072 children in California who have an open child welfare or probation supervised placement within the so-called child welfare system. The child welfare system, or more accurately, the family regulation system, breaks apart families, and punishes marginalized people. The system is rooted in a history of state sanctioned racial violence.

Specifically, the racist family regulation system disproportionally targets Black families endangering the well-being and safety of Black children for generations to come. In practice, the family regulation system shatters the lives of both children and adults by exposing families to long lasting generational trauma, negatively impacting both the physical and mental health of all involved.

Through a collective power we strive to urge California legislatures to take action to protect families from the oppressive practices of the family regulation system. We believe in empowering families across California, and that is why we are introducing a family bill of rights, to protect our children and their futures.

https://familiesresist.com/families-resist-handbook

Capitol West Steps

Sacramento, CA

May 11, 2022